Islamabad is currently going through a severe windstorm, second one in less than a week. On Saturday, heavy rainfall accompanied by gusty winds and hail struck the federal capital, causing water accumulation in several low-lying areas and widespread falling of trees. Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are facing similar weather patterns, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) has issued a warning that severe dust storms are expected from May 27 till June 1 in Western and Southern Pakistan, especially Balochistan.

It has become common parlance to attribute intense weather phenomena to “climate change,” and most Pakistanis have heard the familiar political refrain that the country ranks atop the list of most vulnerable countries to climate impacts. However, for most, these new and stronger storms might still be as confusing as they are terrifying.

READ MORE: National Awards: Violation of Article 259-or Cronyism ?

While tackling the effects of climate change will require action on both a national—and indeed, global—scale, this piece aims to make sense of the madness unfolding before us.

WARMER WEATHER MEANS MORE ENERGY FOR THE STORMS

Every extra fraction of a degree of global warming means a higher amount of moisture to the air. Warmer weather means that water on the earth’s surface as well as warmer seas evaporate faster, pumping more water vapour upwards. This water vapour is the primary fuel of storms, because it’s the condensation of this water at higher altitudes that releases latent heat.

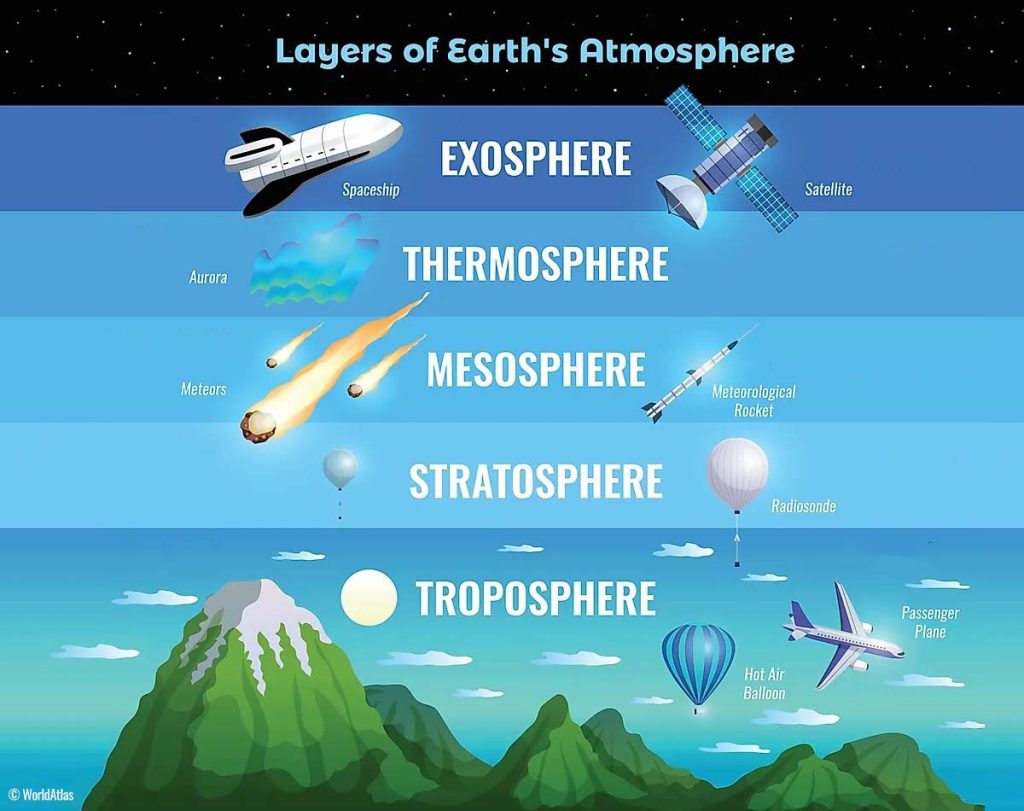

A rather jargon-filled explanation is necessary to describe the next stage of the process. When the bottom part of the troposphere (see refence image) gets hotter, the difference between the warm air in the lower part of this layer and the cooler air in the upper part of this lawyer becomes steeper. This difference fuels storms even more. In scientific terms this is called “CAPE”. CAPE is the “lift” that lets storm clouds soar higher and spin faster. So, as the climate gets warmer, the sky becomes more ready to make stronger winds and bigger hail.

RISING OCEAN HEAT KICKS TROPICAL WINDSTORMS UP A NOTCH

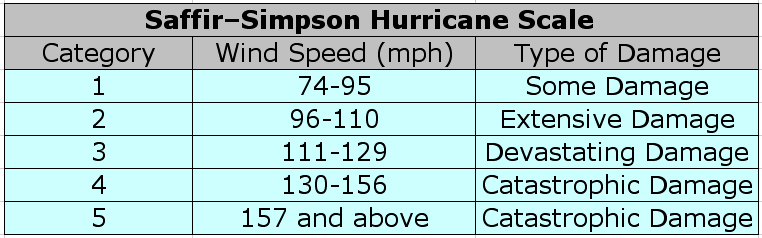

Recent studies have shown the link in real numbers. Nonprofit news organization on climate science ‘Climate Central’ published a report in 2024, showing that human-driven ocean warming added nearly 18 mph to the winds speed of four out of five Atlantic hurricanes between 2019 and 2023, and to every hurricane in 2024. This much hike in speed is enough to change an entire Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale category, turning a “nasty” Cat 2 into a catastrophic Cat 3.

Similar explanation can be given for the stronger windstorms currently sweeping across Pakistan. Warmer water bodies can provide that extra amount of energy for winds that can lead to much stronger and faster wind speeds, leading to falling trees and damaged infrastructure.

Climate models are now run at much higher resolution than a decade ago, and they can now reliably confirm that future windstorms are likely to pack stronger peak gusts, even if the number of storms might not increase. The takeaway: fewer days may see a named storm, but the windy days we do get will be nastier.

HAILSTORMS ARE NO DIFFERENT

Hail forms inside the towering cores of severe thunderstorms, when the water vapors have risen high enough to become super-cooled water. The pressure of the wind and up-draughts keep that ice aloft. The stronger an up-draught gets, the more time hailstones get to grow bigger and fatter before gravity finally wins. [Up-drought is the air current flowing upwards. Warmer air is lighter so when the overall temperature rises, it also pushes upward the air upwards with greater intensity.]

With the core temperature steadily increasing, the up-draughts become more common and more intense, which results in keeping those pebbles trapped longer while increasing in size. High-resolution storm-tracking work released in March 2025 found something even worse – not only the area affected by hail will continue to expand with higher temperatures, but the incidence of giant hailstones (usually 5 cm or above) could also double by mid-century. European Severe Storms Laboratory reports a remarkable 267% increase in documented hailstorms over the past five years.

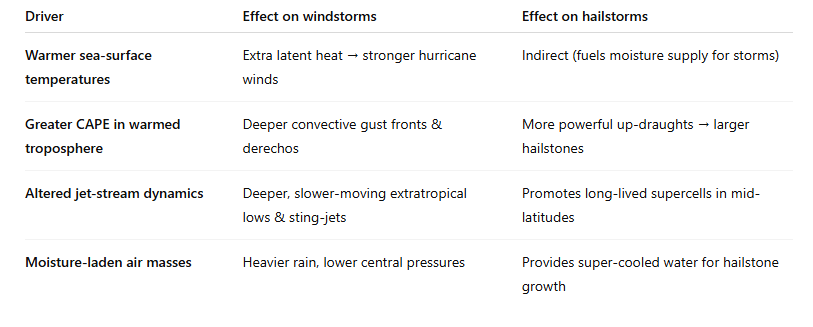

(Table for quick reference; not exhaustive.)

WHAT LIES AHEAD, WHAT WE CAN DO?

Even if global warming were halted today, the heat already stored in oceans guarantees several decades of elevated wind-storm and hail risk.

The factor to be more terrified of might not be the frequency of these weather phenomenon, but their intensity. The number of windstorms and hailstorms might increase or decrease, but the strength and the potential destruction from these events is the bigger cause for concern.

In Pakistan, the storms causing trees or electric poles to uproot might not be a new phenomenon, but the falling canteen roofs and the flying solar panels is something that makes the impact of this rising intensity more and more visible. A slight nudge in the thresholds of average wind speed can make a complete overhaul necessary for design limits of architecture – roofs, turbines and even transmission lines.

READ MORE: Finance Minister Highlights Climate Resilience Initiatives

That said, mitigation still matters the most. Capping warming at 1.5°C versus 2°C can potentially cut the projected increase in the destructive potential of windstorms and hail storms in half. It may also trim the surge in very large hail by a third. Every tonne of CO₂ we avoid, can translate into keeping houses in a small town intact.

BOTTOM LINE

Climate change cannot conjure storms on its own. It loads the dice, so that when nature rolls, devastating wind speeds and cricket-ball hail come up far more often. Understanding the process can allow us to not only predict where and when the punches will fall but will also equip us better to act on that knowledge. Emissions cuts and sturdier infrastructure, is how we make sure the next roll is a little less brutal.